The transformation toward a more sustainable form of enterprise and development began in the 1990’s with the “eco-efficiency” revolution when, for the first time, it became clear that reducing waste, emissions, and pollution could actually save money and lower risk. Eco-efficiency was complemented by the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and corporate initiatives in “social responsibility” aimed at addressing some of the more obvious and egregious social inequalities resulting from globalization. But as important and groundbreaking as these innovations have been, they have succeeded only in slowing the inevitable arrival of the Reckoning…

In 1997, I published an article in Harvard Business Review entitled “Beyond Greening: Strategies for a Sustainable World.” The piece was among the first published by the journal on the topic of “sustainable business;” and much to my surprise, it won the McKinsey Award that year as the best article in the journal. The article stressed that while corporate “greening” strategies aimed at incrementally reducing negative environmental impacts and building social legitimacy (e.g. eco-efficiency, CSR projects) were important, they would not be nearly adequate to the challenge (and opportunity) of global sustainability in the decades ahead. Even then, it was clear that “beyond greening” strategies—innovative new clean technologies, and more inclusive business models that included and lifted the four plus billion poor at the base of the income pyramid—would be essential if we were to fundamentally change the course of the global economy, and set it on a path to sustainability.

Now, twenty years later, I write with some good news and some bad news.

First the good news: A growing number of corporations, entrepreneurs, multilaterals and NGOs have launched “beyond greening” business initiatives. Indeed, “clean technology” has become a large and growing investment category with more than a quarter billion dollars of investment each year. And, my 2002 article with C.K. Prahalad entitled “The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid” helped to ignite a new business-led movement described variously as “social entrepreneurship,” “inclusive business,” “sustainable livelihoods,” “opportunities for the majority,” and most recently, “shared value.” And, most recently, the advent of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) has served to reinforce the scale and scope of the social and environmental challenges we continue to face.

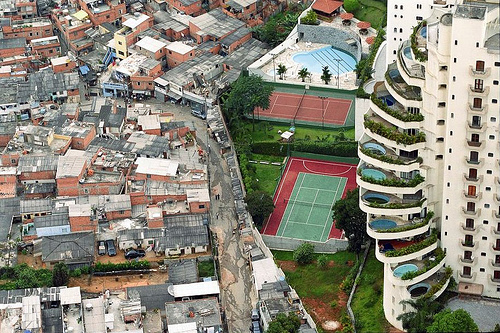

Now for the bad news: We have not yet begun to fundamentally change the unsustainable trajectory of the global economy. Instead, over the past twenty years, we have added nearly two billion more people to the global population and further intensified our ecological footprint on the planet. By 2030, the global “middle class” is expected to grow from the current 2 billion to more than 5 billion people, with the attendant increases in material consumption, waste generation, and greenhouse gas emissions. And while the quest to eradicate extreme poverty is necessary and important, the science is also clear: we have overshot the carrying capacity of the planet and serious repercussions are now inevitable.

To make matters worse, over the past twenty years we have added two new and foreboding crosscurrents to the global sustainability challenge: First, a growing number of people in the developed world that have been left behind by globalization have realized their plight and flexed their political muscles—witness BREXIT in Europe, the rise of Donald Trump in the US, and a growing hostility toward global trade pacts. And second, the global spread of information technology and social media has inadvertently helped to fuel extremist movements, information warfare, election hacking, and misinformation campaigns around the world. The result? Nativism, atavism, protectionism and isolationism are now on the rise at precisely the time that we need more cooperation and multilateralism to address the mounting transboundary challenges that we face—climate change, loss of natural capital, rising inequality, mass migration, and terrorism.

We have thus arrived at the Day of Reckoning for business—and the World. As recent missives from the likes of Larry Fink at BlackRock implore, the time has come for business to finally step up to the plate. With governments in retreat and civil society overburdened, the world is turning to the private sector to address the monumental challenges we now face. The time is now to move beyond “sustainability” as a set of separate but important company initiatives to one of core purpose. We are now past the point where even aggressive clean tech and inclusive, base of the pyramid “initiatives” enable us to change course rapidly enough. Business cannot long thrive within deteriorating environments and failing societies. This means nothing less than refocusing corporate mission and purpose on solving the world’s problems, and building the capabilities and partnership ecosystems to make it happen.

It has now been more than a decade since C.K. Prahalad and I first published the article "

It has now been more than a decade since C.K. Prahalad and I first published the article "

As a co-founder of the new

As a co-founder of the new  Certificate Program in Sustainable Enterprise

Certificate Program in Sustainable Enterprise

In the emerging economies of the world, this revolution has already begun. ITC in India, for example, prides itself on creating livelihoods for the poor in the rural areas as part of its strategy for wasteland reforestation and agricultural productivity improvement. Indeed, as commodity costs rise, it may make sense to redefine productivity--from capital intensity and labor efficiency to labor intensity and capital efficiency. In the 21st century, "sustainable" enterprise must define success by the extent to which they create productive and fulfilling employment for the people of the world.

In the emerging economies of the world, this revolution has already begun. ITC in India, for example, prides itself on creating livelihoods for the poor in the rural areas as part of its strategy for wasteland reforestation and agricultural productivity improvement. Indeed, as commodity costs rise, it may make sense to redefine productivity--from capital intensity and labor efficiency to labor intensity and capital efficiency. In the 21st century, "sustainable" enterprise must define success by the extent to which they create productive and fulfilling employment for the people of the world.