When Franz Schubert wrote the first two movements of Symphony No. 8 in B Minor in 1822 (what would come to be known as the "Unfinished Symphony"),

little did he know that he was modeling the behavior and skills needed to successfully create the markets of the future at the base of the world income pyramid in the 21st century.In fact, a full decade after C.K. Prahalad and I first wrote the

Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid (BoP),

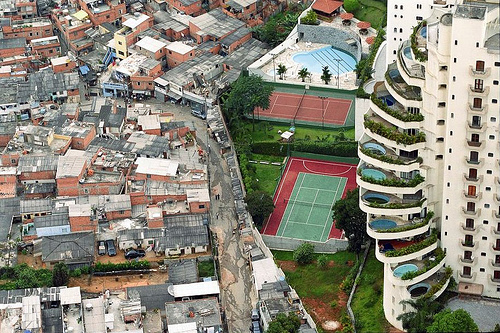

few large corporations have yet to realize the vast business potential of the world's four billion poor and underserved: Most have either sought simply to sell stripped-down versions of their current products to the emerging middle classes in the developing world, or have abandoned the profit motive entirely and moved their BoP initiatives to the corporate social responsibility department or corporate foundation.

Indeed, it is telling that, as we enter the second decade of the 21st century,

the only real BoP business success stories come from the developing world itself--microfinance and mobile telephony for the poor. Billion dollar companies like Grameen Bank and Grameen Phone in Bangladesh, Compartamos in Mexico, and CelTel in Africa still stand out as the few iconic examples of business success cited by BoP analysts and advocates from around the world. In fact, no global conference on the topic is complete without significant reference to at least one of these "home run" examples.

This raises the question:

Is there something about microfinance and mobile telephony that has enabled such stunning success? The answer is yes! When you examine each of these industries closely, it quickly becomes apparent that each is really a

means to an end, rather than an end in itself. Indeed, microfinance and mobile telephony are not end products, but rather are

enabling platforms that facilitate people to accomplish any number of tasks and deliver a wide range of functionalities. They are, in short, the equivalent of "unfinished symphonies."

Microfinanciers and rural wireless service providers enable poor slum dwellers and villagers to figure out for themselves how best to weave these new services into their lives. For these customers, this may mean mobile transfer of funds, communicating in code with a loved one, acquiring a third cow, accurate information on crop prices, or expanding a current micro-enterprise. My colleague

Erik Simanis calls these types of products and services

value open since they enable people to complete the value proposition for themselves.

Unfortunately,

most multinational corporations have chosen BoP strategies that effectively deliver finished symphonies with defined value propositions in the mistaken (though well-intentioned) belief that they know better than the poor themselves what their real needs are. What works in the established markets at the top of the income pyramid, however, does not work so well in the emerging BoP space.

Time-tested marketing research methods (e.g. consumer surveys, focus groups, ethnographic studies) are excellent ways to uncover new opportunities in already established markets, where low cost or differentiation strategies rule and customers are already accustomed to paying money for service. However, when it comes to serving the BoP,

the challenge is not one of uncovering latent demand, but rather one of creating entirely new markets and industries, where only informality, self-provisioning or barter previously ruled. To effectively realize the vast business potential at the base of the pyramid, corporations must thus show a bit of

humility. Companies must come to view the poor more as

partners and

colleagues rather than merely clients or consumers. Such an approach calls for deep dialogue (two-way communication) rather than just deep listening. To realize this mindset shift requires the development of a new "

native capability" which focuses on

co-creating business concepts and business models with the poor, rather than simply marketing inexpensive versions of top-of-the-pyramid products to low income consumers.

The logic of co-creation does not, however, mean simply entering underserved communities with a completely open mind and no sense of business purpose or direction. On the contrary, companies must clearly communicate what resources they bring to the table in the form of skills, capabilities, and technological potential; they must do so, however,

without prematurely imposing a final product or technological solution. The aim then is to marry corporate global best practices and technologies from the company with the local knowledge, skills, and aspirations of the local community--

to complete the "unfinished symphony" together.Done well, such an approach to BoP business development holds the potential to

create entirely new product and service categories that are embedded in the actual context (rather than simply cheaper versions of existing products from the top of the pyramid). Embedding also means creating "

community pull" for BoP innovations, since they have been co-created with community members, rather than engaging in the expensive and time-consuming process of "social marketing" to educate and promote behavior change among the poor.

Over the past seven years, my colleagues and I have been focused on developing such an approach for companies to effectively co-create new markets in the BoP. The approach is called the

BoP Protocol. We have now experimented with this approach in a half-dozen different business contexts in Asia, Africa, and Latin America, and have learned a great deal about how to engage local partners and communities in the dance of co-creation.

Many others have also embarked on similar learning journeys to unravel the keys to successfully creating the inclusive businesses of tomorrow that embrace all of humanity and end the scourge of poverty. My colleague

Ted London and I have gathered some of the most important emerging contributions in this regard in a new book,

Next Generation Business Strategies for the Base of the Pyramid.

Our conclusion: There is no "fortune at the bottom of the pyramid" waiting to be discovered. Instead, the challenge for companies is to learn how to

create a fortune with the base of the pyramid. Franz Schubert's Unfinished Symphony in the 19th century may thus hold the key to a more inclusive form of capitalism for the 21st century.

It has now been more than a decade since C.K. Prahalad and I first published the article "The Fortune at the Bottom of thePyramid" which launched the "BoP" business movement. Over the past decade, there have been fits and starts: many BoP ventures have failed; others have been converted to philanthropic programs; but only a few have taken root and gathered significant commercial momentum.

It has now been more than a decade since C.K. Prahalad and I first published the article "The Fortune at the Bottom of thePyramid" which launched the "BoP" business movement. Over the past decade, there have been fits and starts: many BoP ventures have failed; others have been converted to philanthropic programs; but only a few have taken root and gathered significant commercial momentum.

As a co-founder of the new Indian Institute for Sustainable Enterprise, I aim to do just that--dramatically increase the number and success of entrepreneurs and intrapreneurs focused on socially inclusive and environmentally sustainable business development for the 21st century.

As a co-founder of the new Indian Institute for Sustainable Enterprise, I aim to do just that--dramatically increase the number and success of entrepreneurs and intrapreneurs focused on socially inclusive and environmentally sustainable business development for the 21st century.  Certificate Program in Sustainable Enterprise which aims to create nothing less than a new model of business and entrepreneurial development appropriate to the challenges we face in the 21st century.

Certificate Program in Sustainable Enterprise which aims to create nothing less than a new model of business and entrepreneurial development appropriate to the challenges we face in the 21st century.